Seminar held on 7 November 2020 at the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Jesi, as part of the cycle entitled Interventi intorno Chiari

Influences on Popular Imagery

As is well known, the sixties saw the rise of Pop Rock music with the Beatles, confirming the popular vocation of the entire Contemporary Era since its inception. It is, in fact, within this framework that another of those short circuits typical of this era occurred: if during the 1920s Edgar Varese (1883-1965) eliminated the difference between sound and noise, introducing in his compositions a pressing rhythm and pre-recorded sounds (which also marked the beginning of electronic music) and, in the meantime, Charles Ives (1874-1954) had already introduced musical derivations of popular origin such as ragtime, band music and gospel, then both contaminated classical music with the foreign and the low; In the 1960s, Frank Zappa (1940-1993) reversed the perspective and brought the avant-garde, led by Varese and Ives, who had in the meantime become cultured themselves, back into the popular pop rock sphere. It is no coincidence that in the music of the sixties and seventies the use of noise became increasingly widespread, for example in the production of Pink Floyd, one of the most famous groups of the period.

Left: The Beatles. – Centre: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, 1967 Cover: Peter Blake. – Right: 1967 funeral of the hippie movement against the commercial exploitation of its image, its ideas.

1968 Student revolts 1960s feminist demonstrations

Charles Ives, Edgar Varesse, Jhon Cage, Frank Zappa

Pink Floyd, Atom heart mother

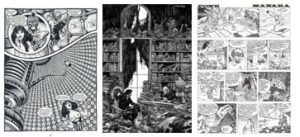

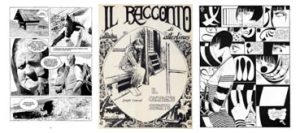

Similar contaminations also occurred in the field of comics in those years. Already at the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s, an author such as Alberto Breccia had introduced into this typically popular medium certain visual influences of the pictorial avant-garde, as well as the use of hybrid materials. An example that would later be taken up in Italy in the creation of the visual alphabet of a well-known character such as Valentina created by Guido Crepax (1933-2003). The language of visual abstraction and an a-chronological narration typical of the literary avant-garde of the psychological novel come into play in her adventures. This latter genre, which between 1910 and 1925, under the influence of Bergson’s (Henri Bergson 1859-1941) thought, centred on the flow of time, and the birth in 1899 of Freud’s (Sigismund Freud 1856-1939) psychoanalysis, blew up the typical narrative construction of beginning – middle – end, where events were presented in an orderly fashion, replacing it with the experiments introduced in the novels of James Joyce (1882-1941), Marcel Proust (1871-1922), Franz Kafka (1883-1924), Thomas Mann (1875-1955) and Italo Svevo (1861-1928).

Alberto Breccia, Mort Cinder, 1962 – Alberto Breccia, Perramus, 1983 – Alberto Breccia, The Man and the Beast, 1981

Guido Crepax, Valentina, 1965

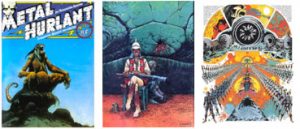

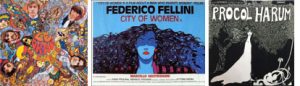

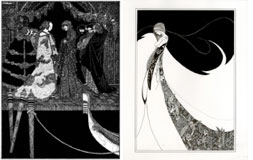

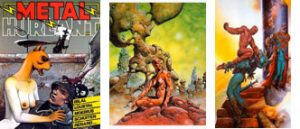

In 1974 in France, the parable of the comic strip magazine Metal Hurlant began, which presented many of the visual values typical of the Hippie culture of the time, expressed above all through an obsessiveness and hypnotism already inherent in the psychedelic music genre in vogue in those years, as well as in the covers of those same LPs (long playing 33 rpm vinyls). In painting, in parallel with Pop Art, Optical Art was all the rage, presenting optical illusions obtained with the same hypnotic obsessiveness. This decorative insistence, albeit with different aesthetic results, is certainly not unrelated to the typical modernism of Art Nouveau in its numerous declinations, more gentle and synthetic as in the case of Beardsley (Aubrey Beardsley 1872-1898), but also more obscure and disturbing as in the case of Henry Clarke (1889-1931).

Left: The first issue of Metal Hurlant, with illustration by Moebius – Centre: Moebius. – Right: Druillet

Magazine founded in 1974 by Jean Giraud (Moebius, cartoonist) with Philippe Druillet (cartoonist), Jean Pierre Dionnet (scriptwriter), Bernard Farkas (financial director), who called the publishing house Les Humanoïdes Associés.

Victor Vasarely, Vega 200, 1968 – Vertigo Recocords 1969 – Axis: Bold As Love – The Jimi Hendrix Experience, 1967

Le Orme, Ad Gloriam, 1969 – Poster designed by Andrea Pazienza – 1967 album

Henry Clarke, Aubrey Beardsley

Metal Hurlant: Enki Bilal, Caza (Philippe Cazaumayou), Richard Corben

Metal Hurlant: Alain Voss, Bernie Wrighyson, Milo Manara

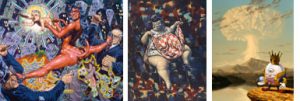

Also in the mid-1970s, in the sphere of American underground comics, Lowbrow painting was born with Robert Williams (1943), a cartoonist who, in his large acrylic canvases, piled up a collection of subjects typical of the popular culture industry along the lines of the previous Pop Art, including, of course, comic strip characters. It is in the 1990s that this current began to take on the characteristics of Pop Surrealism (the name by which it is most commonly known), by which we know it today, as demonstrated by the work of Todd Schorr (1954), whose work up until the end of the 1980s still has a clear Lowbrow imprint, to then change into a painting that presents the more typical pictorial-thematic characteristics of Pop Surrealism and that sees in Mark Ryden (1963) and Ray Caesar (1958) its two greatest representatives.

Left: Robert Williams, The Anti-Madonna’s Affirmation of the Status Quo, 1985. – Centre: Todd Schorr, Fat boy, 1989. – Right: Todd Schorr, Antidoto per un mondo preoccupante, 2012

Mark Ryden, Incarnation, 2009 – Ray Caesar, La Chambre, 2012

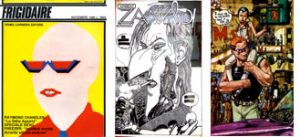

In 1980 the Figidaire experience began in Italy, with the excellent examples of authors such as Andrea Pazienza (1956-1988) and Tanino Liberatore (1953), to name but two. Apart from Pazienza’s Zanardi, the other probably best-known character of the comic magazine was Ranxerox. Initially drawn by Stefano Tamburini – who later became only the scriptwriter – with a great experimental charge made of distortions and elongations of the characters and obtained by pulling prints from a photocopier from which the character takes his name (Xerox is a well-known company that produces photocopiers). Ranxerox was then drawn by Liberatore with the hyperrealist imprint that made him famous.

Left: The first issue of Frigidaire, with illustrations by Stefano Tamburini. – Centre: Andrea Pazienza. – Right: Tanino Liberatore

Magazine founded in 1980 by Stefano Tamburini (cartoonist and script-writer), Filippo Scozzari (cartoonist and script-writer), Vincenzo Sparagna (editor), following the experience of Cannibale (another magazine published by Il Male) to which were added Pazienza, Liberatore and Mattioli, published by Primo Carnera Editore.

Massimo Mattioli, Filippo Scozzari, Stefano Tamburini

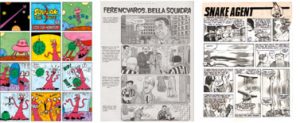

In the 1980s, the Valvoline Group was formed, which had a privileged space in the pages of Aletr Alter, previously Alter Linus, under the direction of Oreste Del Buono (1923-2003, close to the positions of the Gruppo ’63). The reference to the historical avant-garde is more evident than ever in the works of the Valvolinians, especially in the comics by Mattotti (Lorenzo Mattotti 1954), Igort (Igor Tuveri 1958) and Carpinteri (Giorgio Carpinteri 1958). Marcello Jori (1951), a cartoonist better known as an artist and exponent of the Nuovi Nuovi, led by Renato Barilli (1935), already a member of the Gruppo ’63, also belonged to the group.

Lorenzo Mattotti, Igort (Igor Tuveri), Giorgio Carpinteri

The magazine was founded as Alterlinus in 1974, in 1977 it came out as Alter Alter, and in 1983 the Valvoline Group joined it. Oreste del Buono, the director, assigned the editor of one of their inserts: Lorenzo Mattotti (cartoonist and illustrator), Daniele Brolli (writer), Giorgio Carpinteri (cartoonist and architect), Igort (cartoonist), Jerry Kramsky (Fabrizio Ostani, scriptwriter and caretaker), Marcello Jori (cartoonist and artist).

Marcello Jori, Dino Battaglia, Guido Crepax, Valentina, 1965

Bibliography

AA.VV., Desideri in fiorma di nuvole. Cinema e fumetto, Paisan di Prato (UD), Campanotto Editore, 1996.

AA.VV., Gulp! 100 anni a fumetti, Milano, Electa, 1996.

AA.VV., Nuovo fumetto italiano, Milano, Fabbri Editori, 1991.

ANTOCCIA Luca, Il viaggio nel cinema di Wim Wenders, Bari, Dedalo Edizioni, 1994.

ARGAN Giulio Carlo, L’arte moderna 1770/1970, [1970], Firense, Sansoni Editore, 1982.

ARNHEIM Rudolf, Arte e percezione visiva, [1954], Milano, Feltrinelli, 2002.

AUMONT Jacques MARIE Michel, L’analisi dei film, [1988], Roma, Bulzoni Editore, 1996.

BAIRATI Eleonora – FINOCCHI Anna, Arte in Italia, volume 3, [1984], Torino, Loescher Editore, 1991.

BARBIERI Daniele, I linguaggi del fumetto, Milano, Bompiani, 1991.

BARILLI Renato, Il cilclo del postmoderno. La ricerca artistica degli anni’80, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1987.

BARILLI Renato, Informale oggetto comportamento 1. La ricerca artistica negli anni’50 e’60, Milano, Feltrinelli, 1979.

BONITO OLIVA Achille, L’ideologia del traditore – Arte, maniera, manierismo, [1976], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1981.

BORDONI Carlo FOSSATI Franco, Dal feuilleton al fumetto. Generi e scrittori della letteratura popolare, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

BOSCHI Luca, Frigo valvole e balloons. Viaggio in vent’anni di fumetto italiano d’autore, Roma-Napoli, Edizioni Theoria, 1997.

BOURRIAUD Nicolas, Il radicante, [2009], Milano, Postmedia, 2014.

BRANCATO Sergio, Fumetti. Guida ai comics nel sistema dei media, Roma, Datanews Editrice, 1994.

CALVESI Maurizio, Le due avanguardie. Dal Futurismo alla Pop Art, Bari, Laterza, 1991.

CARA Giovanni, Scrittori e popelin, Civitanova Marche, Gruppo Editoriale Domina, 2003.

CAROCCI Giampiero, Elementi di storia – L’Età delle rivoluzioni borghesi, volume 2, [1985],

CAROLI Flavio, Magico primario, Milano, Gruppo Editoriale Fabbri, 1982.

CASETTI Francesco DI CHIO Federico, Analisi del film, Milano, Bompiani, 1990.

COSTA Antonio, Il cinema e le arrti visive, Torino, Einaudi, 2002.

DEBENEDETTI Giacomo, Il Romanzo del Novecento, [1971], Milano, Garzanti Editore, 1989.

DEL GIUDICE Daniele, Staccando l’ombra da terra, Milano, Edizione CDE, 1994.

DEL GUERCIO Antonio, Storia dell’arte presente, Roma Editori Riuniti, 1985.

DE MICHELI Mario, Le avanguardie artistiche del Novecento, [1986], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1988.

DE VECCHI Pierluigi CERCHIARI Elda, Arte nel tempo, [1991], Milano, Bompiani, 1996.

DE VINCENTI Giorgio, Andare al cinema, Roma, Editori Riuniti, 1985.

DORFLESS Gillo, Ultime tendenze nell’arte d’oggi, [1961], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1985.

FAETI Antonio, Guardare le figure, [1972], Roma, Donzelli Editore, 2011.

FARNÉ Roberto, Iconologia didattica – le immagini per l’educazione dell’Orbis Pictus a Sesame Street, [2002], Bologna, Zanichelli Editore, 2006.

FAVARI Pietro, Le nuvole parlanti. Un secolo di fumetti tra arte e mass media, Bari, Edizioni Dedalo, 1996.

FRESNAULT-DERUELLE Pierre, I fumetti: libri a strisce, [1977], Palermo, Sellerio Editore, 1990.

FREZZA Gino, La scrittura malinconica. Sceneggiatura e serialità nel fumetto italiano, Firenze, La Nuova Italia, 1987.

GUGLIELMINO Salvatore, Guida al novecento, [1971], Milano, Editrice G. Principato s.p.a., 1982.

HARVEY David, La crisi della modernità, [1990], Milano, Il Saggiatore, 1997.

HONNEF Klaus, L’arte contemporanea, Köln, Taschen, 1990.

HUGHES Robert, Lo shock dell’arte moderna, Milano, Idealibri, 1982.

KUBLER George, La forma del tempo, [1972], Torino, Einaudi, 1989.

LYOTARD Jean-François, La condizione postmoderna, [1979], Milano, Feltrinelli, 1990.

LYOTARD Jean-François, Peregrinazioni. Legge, forma, evento, [1988], Bologna, Il Mulino, 1992.

MALTESE Corrado, Guida allo studio della storia dell’arte, [1975], Milano, Mursia, 1988.

MALTESE Corrado, Storia dell’arte in Italia 1785-1943, [1960], Torino, Einaudi, 1992.

MENNA Filiberto, La linea analitica dell’arte moderna, [1975], Torino, Einaudi, 1983.

MILA Massimo, Breve storia della musica, [1963], Torino, Einaudi, 1993.

MONTANER Josep Maria, Dopo il movimento moderno. L’architettura della seconda metà del Novecento, [1993], Roma, Laterza, 1996.

PALLOTTINO Paola, Storia dell’illustrazione italiana, [2010], Firenze, VoLo Publisher, 2011.

PELLITTERI Marco, Sense of comics, Roma, Castelvecchi, 1998.

PRIGOGINE Ilya, Le leggi del caos, Bari, Laterza, 1993.

RAFFAELI Luca, Il fumetto, Milano, il Saggiatore, 1997.

REY Alain, Spettri di carta, [1982], Napoli, Liguori, 1988.

RICCIARDI Enrica, Il cuore delle nuvole. Arte figurativa e fumetto, Paisan di Prato (UD), Campanotto Editore, 1996.

RICOEUR Paul, Tempo e racconto 2. La configurazione nel racconto di finzione, [1984], Milano, Jaca Book, 1994.

RICOEUR Paul, Tempo e racconto 3. Il tempo raccontato, [1985], Milano, Jaca Book, 1988.

SCARUFFI Piero, Guida all’avanguardia e New Age, Milano, Arcana Editrice, 1991.

VALLI Bernardo, Lo sguardo empatico. Wenders e il cinema nella tarda modernit´, Urbino, Edizioni Quattroventi, 1990.

VALLIER Dora, L’arte astratta, Milano, Garzanti, 1984.

WORRINGER Wilhelm, Astrazione ed empatia, [1908], Torino, Einaudi, 1975.

Website

CAMPA Riccardo, Dal postmoderno al postumano: il caso Lyotard, in Letteratura-Tradizione, volume 42, 2008, https://ruj.uj.edu.pl/xmlui/handle/item/58854

http://www.treccani.it/vocabolario/https://it.wikipedia.org

https://it.wikipedia.org